Every so often, a place bubbles back into consciousness

Over the past few weeks, Knoydart has surfaced in several unrelated conversations, reminding me of a solo backpacking trip I did there that I’d almost forgotten about.

According to the Mountain Walking Experience logbook I kept for my Summer Mountain Leader award, I did this adventure in July 1995. The same logbook helpfully reminds me that I didn’t gain my Silver Navigation Award until 1997, and my Gold in 1998, so quite how I thought I was qualified to take on that kind of trip solo in the wilds of Knoydart is anyone’s guess. My own guess is a combination of over-confidence and naïveté which would fit the standard genesis pattern for most of my adventures.

Before I Set Off

I wasn’t a complete beginner. A few years earlier I’d begun the challenge of climbing all the hills over 2,000 feet in England which I completed the next year on my 40th birthday so I’d clocked up a fair bit of experience. But most of that had been shared with my then-partner Roy, who’d taken the lead on planning and navigation, finding suitable wild camp spots and organising food and supplies.

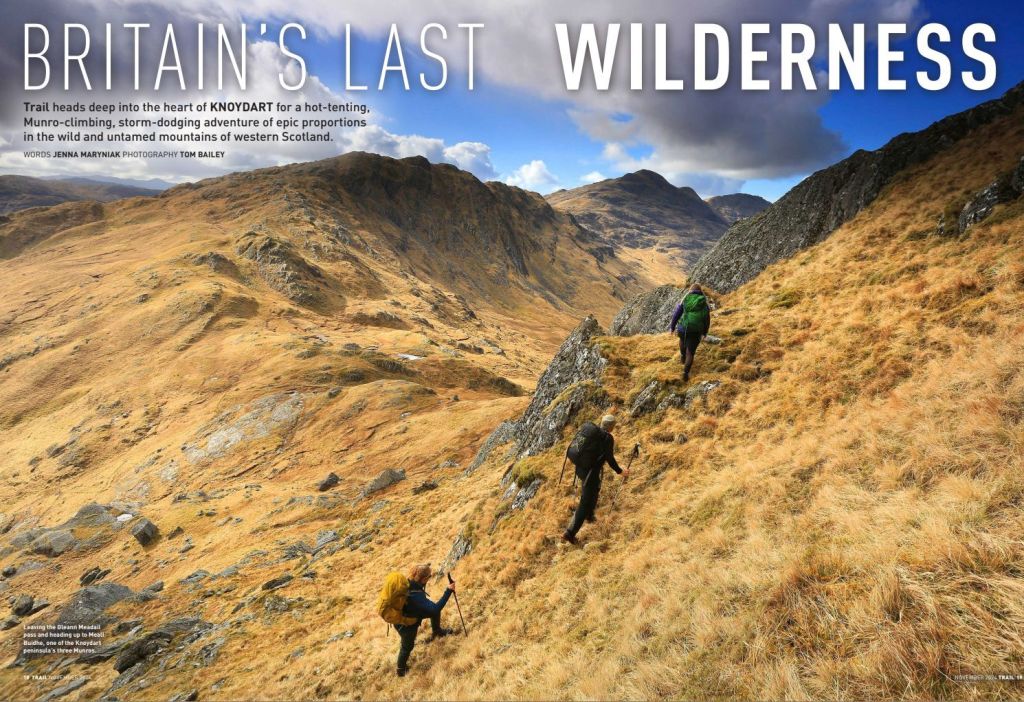

Back then, inspiration didn’t come from Instagram reels or YouTube vlogs. It came from conversations with mountain-walking friends and the pages of Trail magazine and I’m almost certain it was that magazine that first planted the idea in my head.

Some beautiful photographs, and an achievable route. Roy was off having his own adventure on the Annapurna Circuit in Nepal and so I had some spare time on my hands.

How hard could it be?

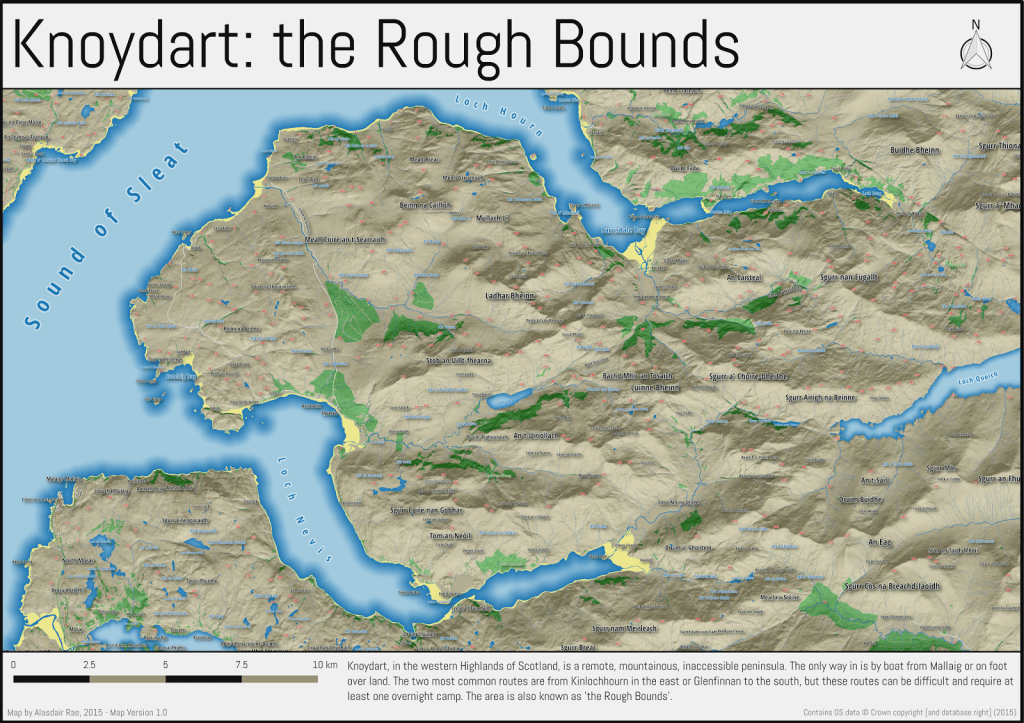

Knoydart: A Wild Peninsula

Knoydart sits on the west coast of Scotland, tucked between Loch Nevis and Loch Hourn, and often described as one of the last true wildernesses in Britain. There are no roads in; it’s only accessible by boat from Mallaig or by a long walk-in over the hills. That sense of remoteness is part of its pull.

Much of the walking here is off-path or on rough tracks, often boggy, sometimes indistinct, and always requiring a good sense of direction, especially when the cloud comes in. But for all that, it’s not a technical area in a mountaineering sense. The challenge lies more in the combination of isolation, exposure to the elements, and the physical effort needed to move through the landscape. It asks a lot but for those prepared to meet it, Knoydart offers a rare kind of reward.

A Different World

In 1995, when I did my trip, there were no smartphones, so no GPS apps or digital maps. Navigation meant paper map and compass, full stop. No phone also meant no 999 calls, but I imagine I had a whistle and maybe some flares.

Planning for a full week on my own in the Scottish Highlands meant carrying everything: tent, sleeping bag, stove, clothes, and enough food to last seven days and six nights. Resupply wasn’t an option.

I must have had a camera, because I’ve found two photographs to share in this post – how times have changed! This one taken outside Sourlies Bothy shows me with my pack.

My Gear

The rucksack was a purple Karrimor Alpiniste 65. Just one big compartment, a floating lid with a zip pocket. Thick Cordura fabric that could take a battering, even in Scottish weather. No mesh, no airflow system, just practical, streamlined design.

To keep that design form intact, I lined it with a rolled-up foam sleeping mat and packed my sleeping bag and clothes into the hollow core. Tent poles down one side, and a black plastic caving drum lashed tightly on top, carrying my Trangia stove, fuel and food.

It certainly wasn’t lightweight, but it was self-contained and compact, ready for whatever the hills threw at me.

Crossing the Water: Into Knoydart

Getting to Knoydart meant first getting to Mallaig, then catching the ferry across Loch Nevis to Inverie. In 1995, that was the MV Western Isles, a sturdy, no-nonsense passenger boat run by Bruce Watt Cruises, a small, family-run outfit that had been serving the area since the 1950s.

The crossing itself felt like a gentle uncoupling from the rest of the world. As the harbour slipped behind and the sea loch opened out ahead, I remember a sense of both anticipation and unease carrying a full pack, a week’s worth of food, and a sense that the usual safety nets were now firmly behind me.

From Inverie, the track east climbs gently at first, winding past a few scattered houses and out into wilder country. The sea falls away behind you, and before long, the last signs of habitation are gone. It’s not dramatic straight away, more a slow, steady unravelling of the human world.

Up to Mam Barisdale

The path follows the glen alongside the Inverie River, hemmed in by hills on either side, gradually climbing towards the heart of the peninsula. It’s a long, steady pull, and then a steeper ascent towards my first objective, Mam Barisdale.

The Mam is a high bealach (mountain pass) between the Knoydart and Barisdale sides, a natural crossing point in the horseshoe of hills.

It took the best part of five hours to get there. I found a flat-ish spot near the top, sheltered enough from the wind, I thought, and pitched my tent.

The plan was to rest, but instead, I found myself drawn uphill again, without a full pack, and I followed the enticing ridge westward towards Ladhar Bheinn. I didn’t make the summit, the mist had settled in and it felt like too big a risk for this first day, and it didn’t matter. I returned to my tent feeling pleased with myself, tired, happy, and quietly astonished that I’d pulled it off, even just that first day.

I returned to the tent as the light faded, had a warm drink, and settled in for the night feeling quietly pleased with myself. First day done. Tent up. Ridge walked. I was tired but content.

Storm on the Bealach

Sometime in the small hours, I was woken by the sound of the tent flapping violently. A storm had blown in — fast, loud, and with no sign of letting up. The wind came in waves, rattling the fabric and shaking the poles.

I lay there for a while, listening, trying to gauge whether it would pass. I had a small radio with me, and for the first time I really tried to make sense of the shipping forecast. Names like Dogger, Viking, Cromarty. I tried to picture where they were, and what the forecast actually meant. “Veering northwest, backing later.” It felt like they were mysteries I could have done with unravelling before this trip and would certainly put on my curriculum afterwards.

Eventually, I sat up, pulled on all my clothes, strapped on my head torch, and began packing what I could in the cramped space, just in case. If the tent went, I didn’t want to be scrabbling around in the dark for essentials. There wasn’t much sleep to be had after that.

By around 4am, I unzipped the door to assess the situation, I realised I could just about see the start of dawn filtering through the cloud. That tiny shift made all the difference. I packed up the tent as quickly as I could. Once I’d made the decision to go, there was no turning back. I just needed to get off the hill.

Barisdale Bothy

The descent from Mam Barisdale felt longer than it should have. Every step was cautious, deliberate — boots skidding slightly, shoulders aching under the damp weight of the pack. It wasn’t frightening, exactly, just relentless. By the time I reached the Barisdale bothy, I was soaked through and utterly windswept.

I opened the door to find a room full of people: dry, warm, clearly going nowhere. They looked up, slightly wide-eyed, mugs of tea in hand, boots off, books open. It was obvious they’d made a very different call the night before. I’m not sure what they thought of me appearing out of the storm like some dripping, flustered apparition.

I gave a sheepish nod and found a space to peel myself out of my wet layers, grateful just to be indoors.

A Wild Way to Sourlies

It wasn’t how I’d imagined the second day beginning, but then again, nothing about Knoydart was following any script. And in a way, that was exactly what I’d come for.

Whilst waiting to dry off, I got chatting to a man who was hiking with his son. I made the mistake of agreeing that it would be wise to head over to Sourlies Bothy that evening. Later, I was to rue this conversation because as the weather cleared, I thought I might head back to climb Meall Bhuidhe which had been my original intention for this day before the storm hit.

I did start to head back up Mam Barisdale but then felt that I was committed to getting to the bothy in case it caused some concern and I was reported missing. Instead I followed the ridge up to the flanks of Luinne Bheinn. It was a high, quiet place with sweeping views back down Glen Barrisdale and, in the distance, the ridge of Ladhar Bheinn I’d left behind the day before.

From there, I dropped down below Ben Aden and eventually arrived at Sourlies Bothy. It had been a beautiful walk and now the weather had cleared I was able to fully appreciate the wildness of Knoydart.

Arrival at Sourlies

By the time I reached Sourlies, it was early evening. The bothy stood as it always has, squat and weathered just above the shore, looking out across the wide sweep of Loch Nevis, a sea loch that breathes with the tides.

One concern about arriving at a bothy is – will there be enough space? Sourlies in particular is a fairly easy walk in from Inverie so can get quite busy. It only sleeps 8 people, cosily. When I arrived, as well as the father and son I’d met at Barisdale, a group of young lads were already there so I opted to pitch my tent in the space in front of the hut.

The lads had been down on the rocks at low tide, collecting mussels, and they set a fire going in the lee of a boulder, well away from the bothy. They invited me over, offering me some of their mussels, and passing round a bottle of whisky.

No garlic, no recipe — just sea-water steamed shellfish and laughter shared around the fire. It’s a good memory.

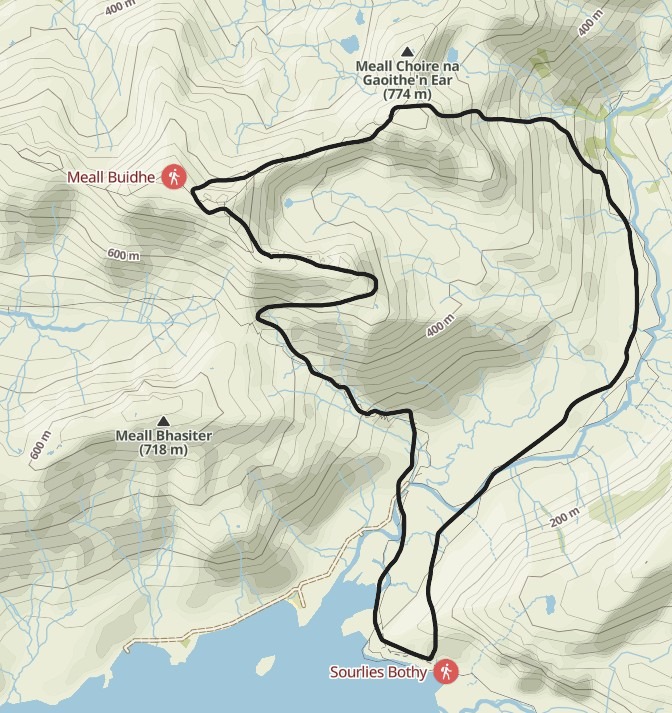

Day Walk to Meall Bhuidhe

Other bits of my memory are a bit hazy, but I’ve logged that I did climb Meall Bhuidhe on this trip. It seems to make sense that after the adventures of the night before, I could have stayed at Sourlies bothy another night and bagged this Munro on a day walk.

Looking at the map now there seems to be an obvious option for a good day’s walk especially without a heavy pack. From the bothy, I would have followed the glen inland, keeping to the faint path along the River Carnach. It would have been boggy in places, but the route was clear enough: the land gradually rising, the hills closing in.

At one point when I was walking across rough ground, almost near the summit of Meall Buidhe, I pulled myself onto a broad shelf and found myself face to face with a huge eagle’s nest. Fresh feathers, clean white droppings, definitely in use. It was fascinating to see, but I didn’t think it was a good place to linger. I backed off quietly and found another line.

I’m not entirely sure, but I think the walk along the ridge to Meall Choire na Ghaoithe’n Ear (‘Hill of the Corrie of the Eastern Wind’) would have been too tempting to resist. So, I’m taking the route of artistic licence and saying I did it, then dropped back down into the river valley and returned to Sourlies Bothy. This time, I had it to myself. Given that both bothies had been busy, I now reckon those must have been weekend nights. From this point on, I didn’t see another soul.

Sourlies to Glenfinnan – Following the Shape of the Land

Again, I can’t be completely sure this was the route I took, but I’ve noted in my mountain log that I climbed another Munro, Sgurr Na Ciche, and looking at the map now, tracing the lines, recalling the feel of the terrain that would make sense.

Leaving Sourlies Bothy, I’d have followed the ridge behind the hut and climbed steadily up to reach that summit then perhaps over to Sgurr nan Coireachan. That would have involved some walking over rough ground, with a heavy pack. I would have been walking slowly, so at some point, I would have found places to stop to rest and pitch my tent for the night.

By this time, I was midway through the trip—a golden time. Feeling fitter, my pack growing lighter as I worked through my food, and I don’t remember it being hard or a struggle. That may be the benefit of memory, but what I recall is the wonder of being out in the wilderness, alone, surrounded by beauty.

Crossing the High Ground

From Sgurr nan Coireachan, I likely dropped down into Glen Dessary for a wild camp, and then followed the valley down towards Glenfinnan because I remember camping for the last night at Corryhully Bothy, finishing off the last of my food — a mix of noodles, cup-a-soup and dried veg.

The next morning I walked the last few miles to Glenfinnan and a jolt back into civilisation. The station café is a 1950’s Standard Open coach converted into a dining caral and fortunately they served the food I had been craving on the walk in – my usual ‘back to civilisation’ meal, a cheese and onion toastie.

Steam, Spectacle, and Homeward Thoughts

As I waited for the Sprinter train to Fort William, a piper arrived on the platform and began tuning his bagpipes. Then, with a hiss of steam and a gathering crowd, the Jacobite rolled in, the famous steam train that crosses the 21-arched Glenfinnan Viaduct, now a fixture in the Harry Potter films. In 1995, of course, Hogwarts hadn’t yet made its mark, and the spectacle felt less like a scene from a franchise and more like a surreal overlap of worlds.

This journey, which starts (or ends) at Mallaig to Fort William, and then Glasgow, is known as one of the world’s best train journeys. But it was the ordinary Sprinter train that carried me home, and the views were just as spectacular as the ones the steam train passengers had. As the landscape slipped past, moor and mountain, loch and sea and viaduct views, I thought then, as I still do now, that there’s something to be said for being out there in it, boots muddy, pack on your back. Better to be on the outside looking in than on the inside looking out.

“It is not our abilities that show what we truly are… it is our choices.”

— Albus Dumbledore, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

Further Reading & Useful Links

Knoydart Foundation – community, conservation, and local history

Walkhighlands – Knoydart walking routes and maps

Mud and Routes – The Escape from Knoydart

Mountains of England and Wales: Vol 2 England: (The Nuttalls)

The Man in Seat 61 – Scotland’s most scenic railway, The West Highland line